Movie Subway Man Shot in the Back by Police

Ten years after BART police Officer Johannes Mehserle killed Oscar Grant, and six years after the shooting was depicted in the film "Fruitvale Station," the incident is recalled by many observers as the most seismic moment for police accountability since the 1991 beating of Rodney King, which also was caught on video.

The shooting of Grant still ricochets: It touched off a national conversation about racism and police violence and initiated a form of stark, instantaneous documentary in which witnesses capture use-of-force incidents on cell phones and post the footage to YouTube and social media.

Yet it can be easy to forget exactly what happened on that Oakland train platform in the early hours of New Year's Day 2009.

Most everybody knows the outlines — a white officer fires a pistol into the back of an unarmed black man who has been pulled off a train as fellow passengers wield phones and digital cameras to capture the scene, spurring mass protest and a murder trial. The officer says he meant to shock the victim with a Taser, not shoot him.

What people may not know is how many lives changed as a result of that single gunshot. And they may not understand that some of the central facts of the case remain in dispute even today.

Let's take a closer look:

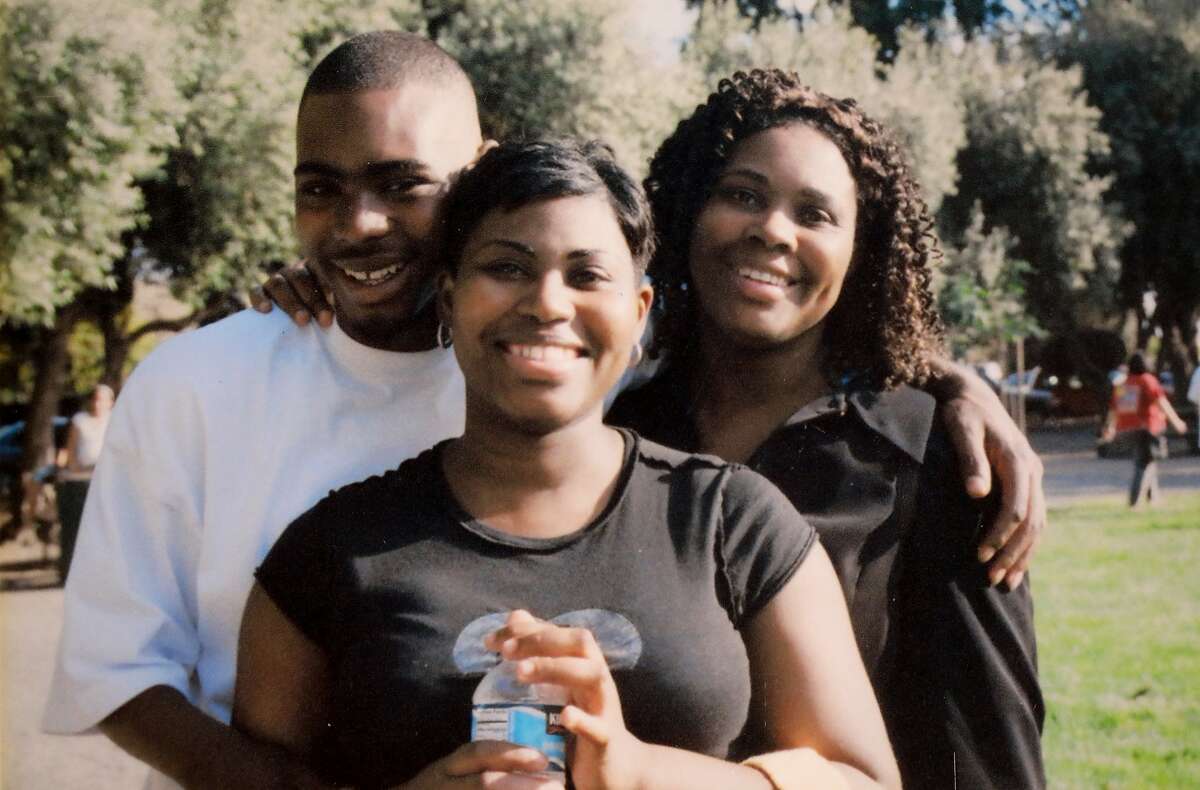

Who was Oscar Grant?

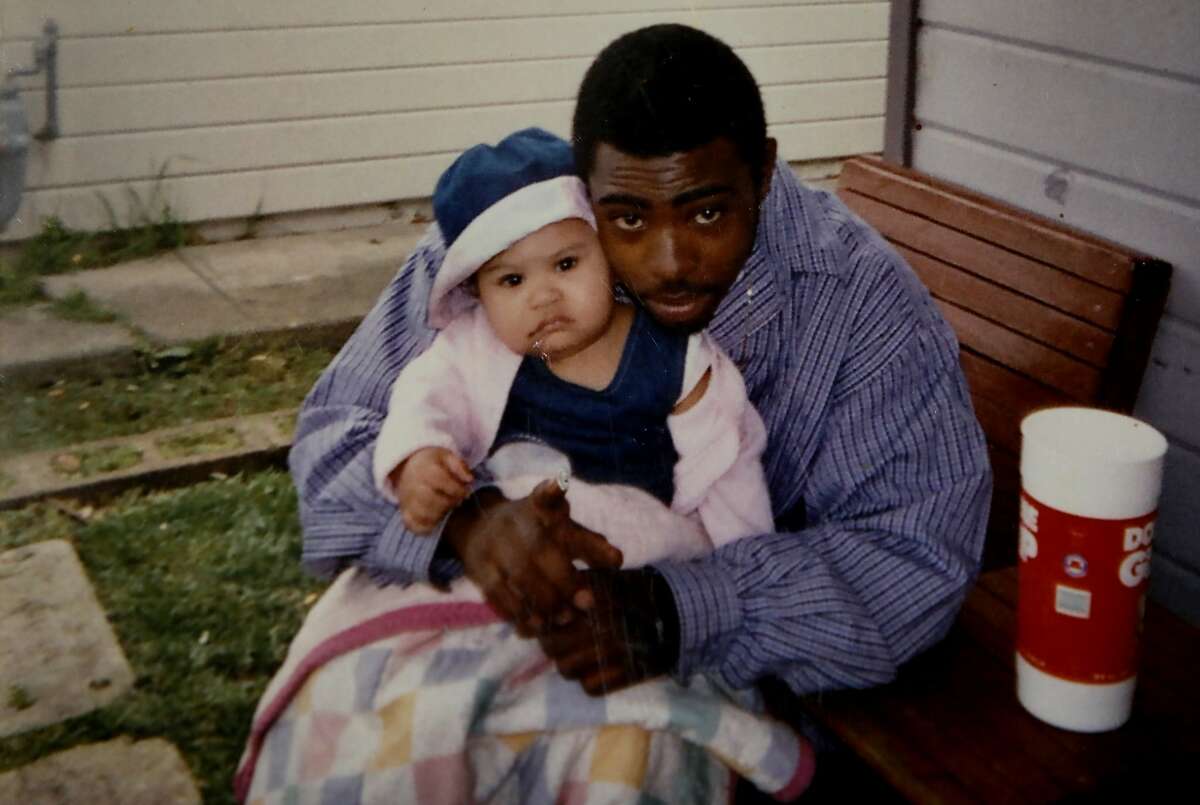

As The Chronicle wrote in 2010, Oscar Grant III became a symbol in death, but in life he was a 22-year-old retail worker and young father. He grew up in Hayward, the son of a United Parcel Service supervisor, Wanda Johnson. She raised him without the help of his father, who is serving a life sentence for murder. Grant worked at KFC, a medicine-delivery service and Farmer Joe's Marketplace in Oakland, but wanted to become a barber.

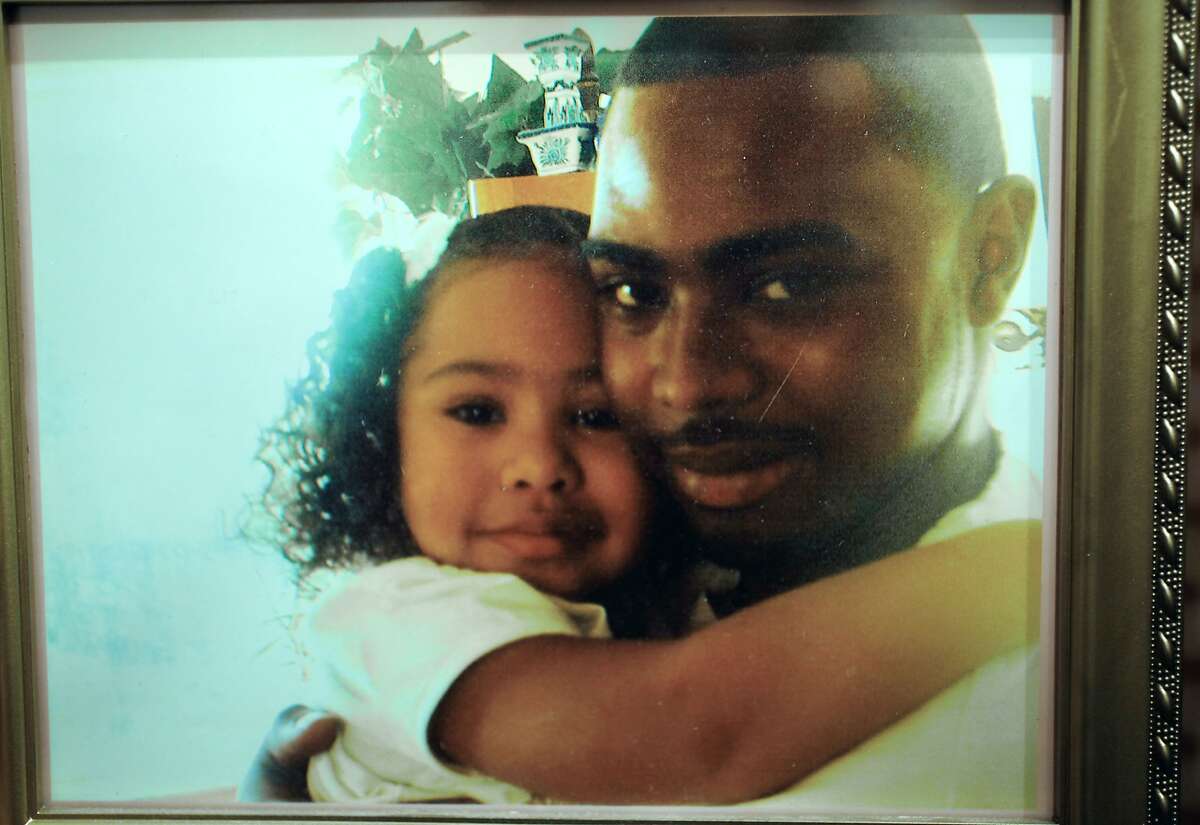

Loved ones described him as a loyal friend and doting father. He got into a fair bit of trouble, serving jail time for crimes, including dealing the party drug ecstasy. He also became a father as a young man — his daughter Tatiana was 4 when he was killed — and planned to marry the mother of his child.

Grant's uncle, Cephus Johnson, said that on Christmas Day 2008, seven days before his death, Grant opened up about his life: "It was clear he was more in the mode of settling down," Johnson said. "He'd done a little time. He was telling me about the bad choices he had made. He said, 'I'm done.'"

Tatiana's mother, Sophina Mesa, said she and Grant had a long talk about their future two days before his death, deciding they would move out of his mother's house in Hayward and get their own place — perhaps in the quieter suburbs of Dublin or Livermore. Grant planned to go to barber school, she said, and "just wanted to change his whole life."

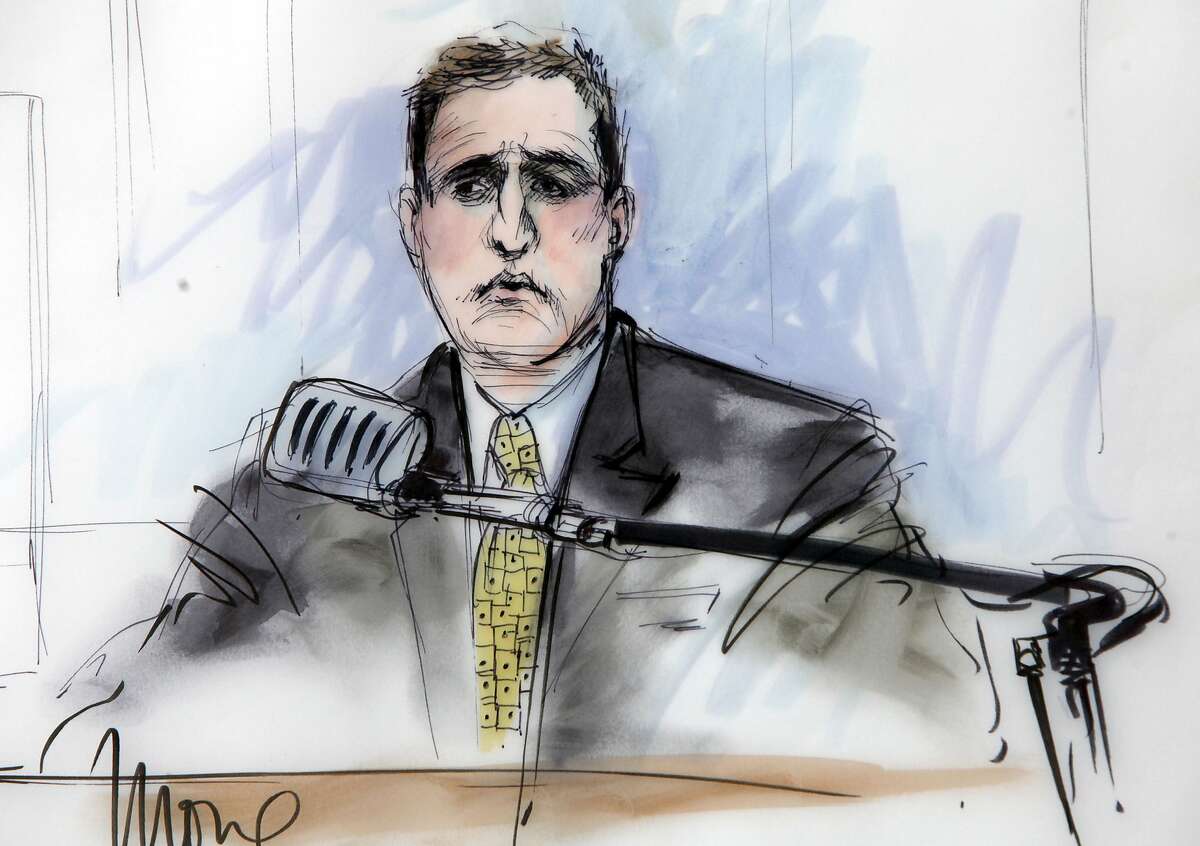

Who is Johannes Mehserle?

Mehserle grew up in Napa and was a 27-year-old Lafayette resident, working as a BART police officer at the time of the shooting. He testified during his trial that he got into law enforcement in 2006 in part based on the recommendation of a friend who had joined the Stockton police force. He wanted to help people, it sounded exciting and the pay was good, Mehserle said. He joined BART in March 2007.

Mehserle had no record of disciplinary problems. Six weeks before he shot Grant, he was one of five BART officers whose arrest of a man prompted an excessive-force lawsuit. A federal jury, however, later cleared the officers of wrongdoing. Mehserle almost wasn't on duty at the time of the shooting because his girlfriend was in the late stages of pregnancy; she gave birth to the couple's first child the next day.

Why did BART police pull Grant off a train?

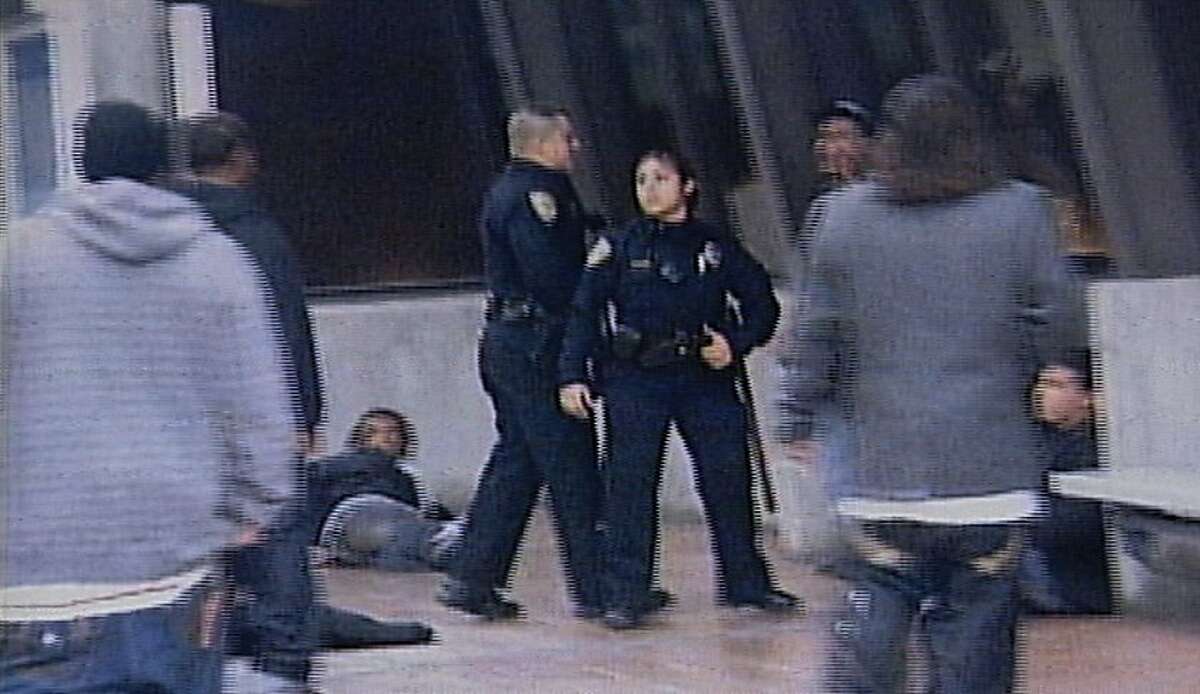

Evidence suggests that BART officers repeatedly violated Grant's rights at Fruitvale Station before he was shot at 2 a.m.

The episode began with a scuffle. Grant was on his way home from San Francisco, surrounded by a group of friends and packed into a train full of New Year's revelers, when he fought with another passenger. Prosecutors identified that rider as David Horowitch, who was once in jail with Grant, though Horowitch, who was then 34, has never spoken publicly about the incident.

People called the police about the altercation, and, at Fruitvale Station, Grant and four friends were detained by BART Officer Anthony Pirone, a thickly muscled Marine who was already at the station with his partner.

According to court testimony and video of the incident, Pirone pulled Grant and his friends off the train so aggressively that other riders loudly objected. Pirone got physical at least two more times with Grant, kneeing him and pulling him violently to the concrete platform. At one point, apparently angry at being called a profane name, Pirone leaned in close to Grant and shouted back at him, "Bitch-ass n—, right? Bitch-ass n—, right?"

Why did BART police arrest Grant?

After Pirone and Grant shouted profanities at each other, Pirone told Mehserle — who had arrived after driving to the station in a patrol car — to arrest Grant for resisting, announcing that "this motherf—er is going to jail."

Video footage, though, suggests Grant had put up little resistance and that Pirone — who was fired for his actions on the platform — had been the aggressor. Alameda County prosecutors called the arrest unlawful. John Burris, an attorney for the Grant family, said Pirone had made a "contempt-of-cop arrest." One person who was on the same BART train as Grant, Marcus Torres, testified in court that when he heard the gunshot, he assumed Pirone had fired it "due to his behavior that evening."

How did the shooting happen?

What everyone agrees on is this: After being instructed to arrest Grant and one of his friends, Mehserle struggled to handcuff Grant while forcing him from his knees to his chest. After about 10 seconds, Mehserle — who later testified he feared Grant might pull a gun, though he was unarmed — unholstered his service pistol, stood up and fired a single shot into Grant's back.

At trial, prosecutors and defense attorneys sparred over whether Grant was resisting Mehserle's efforts to pull his right wrist behind his back. The defense said the resistance is clear in videos, but prosecutors offered a different explanation: They said the officers had awkwardly pinned Grant against the outstretched left leg of one of his friends, Carlos Reyes, who also was detained.

Video footage showed that as Mehserle raised his gun, Pirone had his left knee on Grant's neck. Pirone's left hand was pressing Grant's head into the platform, and Pirone's right hand was holding Grant's right arm — the same one Mehserle said he had struggled with — behind his back.

According to some witnesses, Mehserle announced before the shooting that he was about to use his Taser on Grant. Seconds after shooting Grant, Mehserle put his hands on his head, then moved them to his knees, doubling over. One of Grant's friends testified that moments after the shooting, Mehserle said, "Oh s—, I shot him."

Grant looked at Mehserle and said, "You shot me."

At least three BART passengers captured the shooting on video. Perhaps the clearest footage was provided by Tommy Cross, a 20-year-old San Francisco State University student who recorded what happened on his digital camera. Here is the video:

Now Playing:

Other cameras — including from passengers Karina Vargas and Margarita Carazo — caught all or part of the shooting, as did BART surveillance cameras. At Mehserle's trial, the defense synched six videos to allow the jury to see the incident unfold from multiple angles at the same time. Here is what that looks like:

Now Playing:

And here is how the shooting was depicted in "Fruitvale Station," the 2013 film that dramatized Grant's last day and that helped launch the careers of director Ryan Coogler and actor Michael B. Jordan:

The shooting's aftermath

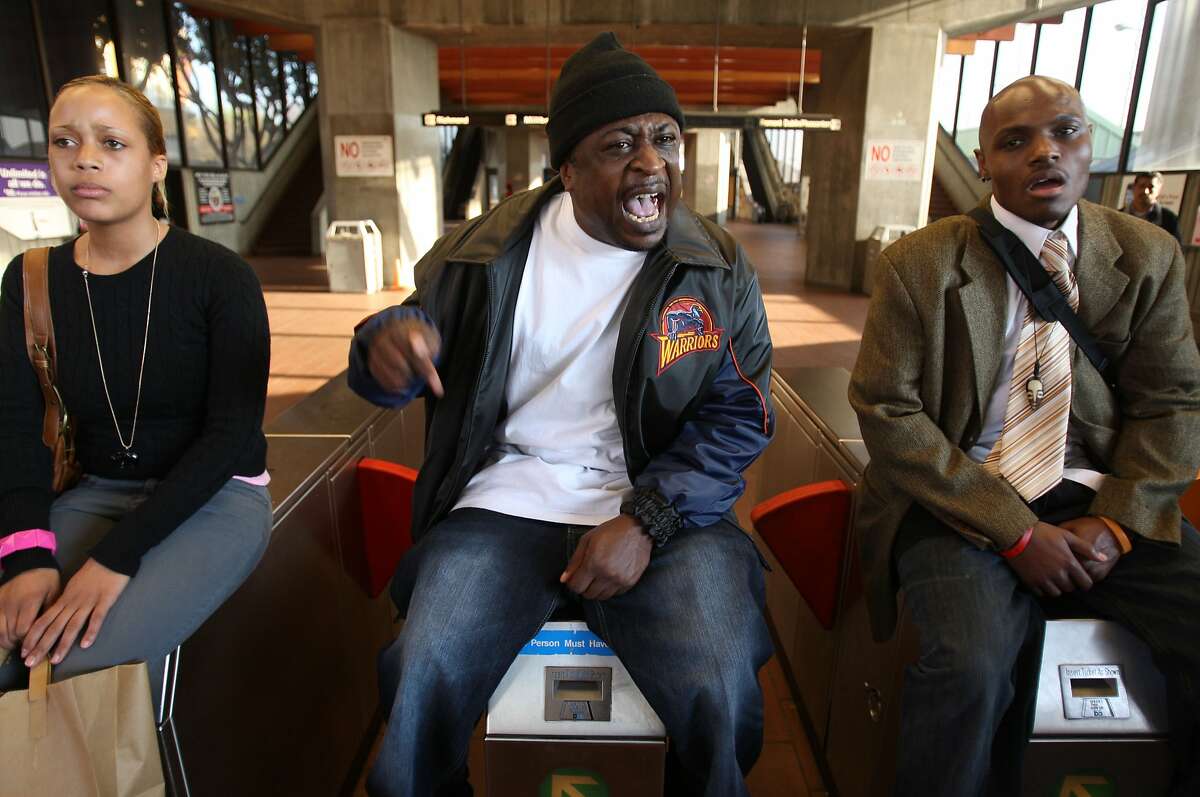

Mehserle resigned on Jan. 7, less than a week after the shooting, avoiding an interview with BART internal affairs investigators. He quit as video recordings made by BART passengers began to air repeatedly on TV news, and as Grant's family prepared a multimillion-dollar lawsuit against BART.

Hours after Mehserle resigned, some protesters marched and others rioted in downtown Oakland, angry about the shooting and that the officer had not been arrested immediately. People smashed storefronts and set cars ablaze while demanding that Alameda County District Attorney Tom Orloff file a murder charge.

"These things normally take weeks rather than days, but I am trying to expedite this and get it resolved as quickly as we can," Orloff, who now is retired, said at the time.

Two weeks after the shooting, Orloff charged Mehserle with murder based on video evidence that he said showed the killing was intentional and unjustified. He noted that Mehserle had refused to talk to investigators about why he shot Grant. Mehserle was arrested at a friend's home near Lake Tahoe, where his attorney said he had gone after receiving death threats in the Bay Area.

After a June 2009 preliminary hearing of the evidence, an Alameda County Superior Court judge ordered Mehserle to stand trial, saying he didn't believe defense attorneys' assertion that Mehserle had mixed up his pistol and Taser. "There's no doubt in my mind," Judge C. Don Clay said, "that Mr. Mehserle intended to shoot Oscar Grant with a gun and not a Taser."

Four months later, another judge moved the trial to Los Angeles, citing extensive media coverage, inflammatory comments by public officials and the specter of possible unrest. Mehserle and his defense attorney, Michael Rains, had received death threats, and someone had fired shots at Rains' Pleasant Hill office overlooking Interstate 680, prompting him and his partners to move up three floors.

Mehserle's defense

At Mehserle's trial, which began in June 2010, the former officer said he did not mean to shoot Grant.

"I didn't think I had my gun," Mehserle testified. "I remember the pop. It wasn't very loud. It wasn't like a gunshot, and I remember wondering what went wrong with the Taser. ... I remember looking to my right side and seeing my gun in my right hand. I didn't know what to think. I just thought it shouldn't have been there."

Rains said Mehserle had no motive to intentionally shoot a man in the back in front of hundreds of witnesses. And he blasted BART for its substandard Taser program: Training had lasted one day, with officers allowed to fire the weapon just once.

Meanwhile, as a cost-cutting move, the agency hadn't bought everyone a personal Taser and Taser holster, instead forcing officers to swap them between shifts. That meant Mehserle couldn't practice drawing the weapon, and that he carried it in whatever holster he could get his hands on — sometimes setting up for a right-hand draw and other times for a draw with his weaker left hand.

Mehserle's actions, the defense said, showed a man trying to use a Taser, including his warning, "I'm going to Tase him." Rains focused on video suggesting that when he reached for his pistol, he struggled to yank it free from the holster. Under the stress of a chaotic platform, Rains said, Mehserle turned to a motor skill — drawing his gun — that had become automatic after thousands of repetitions, rather than to a skill — drawing his Taser — that he had just picked up.

The officer rose to his feet, the defense said, so he could create enough distance between him and Grant for the two Taser darts to spread out and incapacitate Grant. Then he fired just once, even though he was taught that multiple gunshots were often needed to stop a suspect. When he looked at his right hand and saw the gun, Rains said, he recognized his mistake. That's why he shouted, "Oh s—, I shot him."

The prosecution case for murder

Both the district attorney's office and the Grant family believe the Taser story is a fabrication. David Stein, the prosecutor who tried the case, told jurors that no police officer had ever, while wearing a Taser in a holster positioned on his or her weak side, accidentally grabbed a gun from the strong-side hip and fired it.

Mehserle's Sig Sauer P226 pistol was black and weighed 2½ pounds. His Taser X26 was yellow and weighed one-third as much. The Taser had an on-off switch that had to be flipped with the thumb and a laser sight. The pistol had no on-off or safety switch and no laser.

The Safariland gun holster was designed to keep assailants from snatching the weapon, and it wouldn't have come free unless a hood was rocked forward and a lever depressed with the gun-hand thumb. The Blade-Tech Industries holster for the Taser, meanwhile, had a thumb snap that had to be opened.

Prosecutors scoffed at Mehserle's justification for deciding to use his Taser — that Grant, while lying on his chest, appeared to reach for a gun in a pants pocket. Had he believed that, Mehserle would have pinned the hand down or opted for his own pistol, not his Taser, Stein said. He wouldn't have gotten up from his knees and broken contact with Grant, giving Grant a chance to wheel around and fire.

Had he really meant to use his Taser, Stein said, Mehserle would have immediately told those around him. But he didn't tell Grant, and in fact handcuffed him. He didn't tell Pirone, instead explaining, "Tony, I thought he was going for a gun." He didn't tell at least three other officers he spoke to in the 10 minutes he remained on the platform. Finally, after asking a close friend on the BART force to sit with him at police headquarters, he didn't tell him either.

The jury's options

Jurors were given the option of convicting Mehserle of second-degree murder (punishable by a sentence of 15 years to life in prison), voluntary manslaughter (three to 11 years), involuntary manslaughter (two to four years) or nothing at all. For each of the three possible crimes, Judge Robert Perry gave jurors two theories under which they could convict.

Second-degree murder theories: (1) Mehserle unlawfully intended to kill Oscar Grant or (2) intentionally committed an inherently dangerous act, while knowing it was dangerous and acting with conscious disregard for human life.

Voluntary manslaughter theories: (1) Mehserle killed Grant in the heat of passion or (2) acted in "imperfect self-defense," based on an actual but unreasonable belief that he needed to use lethal force.

Involuntary manslaughter theories: (1) Mehserle committed a lawful act but with "criminal negligence" or (2) committed a crime — using excessive force on Grant by deciding to shock him with a Taser — that was not in itself potentially lethal, but became so because of the manner in which it was committed.

The verdict — and a complication

On July 8, 2010, the Los Angeles County jury convicted Mehserle of involuntary manslaughter, suggesting that the panel believed the ex-officer's testimony that he had intended to tase Grant. But there was a confusing twist: Jurors also convicted Mehserle of a separate allegation of "intentionally" firing a gun, exposing him to up to 14 years in prison.

Four months later, Judge Perry threw out the firearm conviction — saying there was no evidence to support it — before sentencing Mehserle to the minimum of two years behind bars. With credit for time served, Mehserle was eligible for release in about seven months. Jurors refused to speak to reporters covering the trial, and have never explained their verdict, including their seemingly contrary decision on the second allegation.

In comments during sentencing that elated the defense and outraged Grant's family, Judge Perry said Mehserle would have been justified in using the Taser because Grant was resisting the attempts to handcuff him. Mehserle's "weapons confusion" was owed in part to BART's poor training of its officers and to "near-riot" conditions at the train station, Perry said. Mehserle, he added, was deeply remorseful.

"Mehserle's muscle memory took over in this moment of great danger and stress," Perry said. "No reasonable trier of fact could have concluded that Mehserle intentionally fired his gun."

In a statement to the court before sentencing, Mehserle apologized directly to Grant's family for the first time and said it was Grant's actions on the Fruitvale platform — not the fact that he was black — that led him to reach for his Taser. "I am deeply sorry," he said. "Nothing I can ever do will heal the wound I have created."

Long recovery for BART

The episode exposed deep shortcomings at BART, which embarked on a series of reforms recommended by the National Organization of Black Law Enforcement Executives, or NOBLE. A study by the group found BART's police force had antiquated policies, a poor relationship with passengers and toothless discipline for officers.

The police chief at the time of the shooting, Gary Gee, retired in August 2009 while suffering from serious medical issues. BART paid $1.5 million and $1.3 million to settle federal civil rights lawsuits filed on behalf of Grant's daughter and mother, respectively.

BART gradually improved, but with some stumbles. In 2014, one of the agency's officers accidentally shot and killed another officer while the two were searching a robbery suspect's apartment in Dublin. Two years later, a Chronicle investigation revealed that more than three-fourths of security cameras inside BART trains were decoys. BART replaced the fake cameras with real ones the next year.

The agency is haunted by Grant's killing, which remains a point of controversy for some BART officials and a deep wound for others. This year, agency staff commissioned an art project to acknowledge this painful part of BART's past, a mural to honor Grant at Fruitvale Station. It's expected to go up next year.

Grant's family also filed an application to rename the station for Grant, and it wants to append his name to a small bus and taxi roadway near the station entrance.

A shooting's long legacy

The shooting profoundly changed the lives of numerous people, including many who were on the platform that night:

•Johannes Mehserle changed his name and his profession. "He's doing fine," Rains said.

•Grant's mother, Wanda Johnson, received $1.3 million from BART to settle a federal civil rights lawsuit she filed shortly after the shooting. She runs the nonprofit Oscar Grant Foundation, a social justice organization started by her brother, Cephus Johnson, who became a dedicated activist. The group seeks to build trust between communities and law enforcement.

•Grant's daughter, Tatiana Grant, now 14, received a $1.5 million settlement from BART over her father's killing. She attends eighth grade at a public school in Castro Valley and plays volleyball and basketball.

•Anthony Pirone was fired in early 2010 for his role in the shooting and was later charged with fraudulently collecting thousands of dollars in unemployment benefits — allegedly collecting money even though he had joined the Army. Alameda County prosecutors, though, dismissed the charge on the eve of trial in 2013, citing a lack of evidence.

•Marysol Domenici, a BART police officer who helped detain Grant and his friends, was fired in 2010 for allegedly lying to investigators and an Alameda County judge about the killing. After a 14-day hearing to contest the allegations, an arbitrator reinstated her job with full back pay. Domenici has since been promoted to sergeant.

•Two of Grant's friends who were with him on the train, Johntue Caldwell and Kris Rafferty, were later slain in street crimes that remain unsolved. Caldwell, 25, was fatally shot while behind the wheel of a car at a Hayward gas station in July 2011. Rafferty, 30, was shot and killed in January 2016 in Hayward. The three friends are buried next to each other in the Lone Tree Cemetery in Hayward.

Demian Bulwa and Rachel Swan are San Francisco Chronicle staff writers. Email: dbulwa@sfchronicle.com, rswan@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @demianbulwa, @rachelswan

Movie Subway Man Shot in the Back by Police

Source: https://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/article/10-years-since-Oscar-Grant-s-death-What-13489585.php

0 Response to "Movie Subway Man Shot in the Back by Police"

Post a Comment